Belfast and (London)Derry – in short, The Troubles…

Belfast had been on my travel bucket list for a looooong time. My initial plans to visit the capital of Northern Ireland were thwarted by COVID, but as I’m stubborn as hell I finally made it there this year. So, why has Belfast intrigued me for so long? There are two reasons: one is quite significant, and the other is rather quirky.

Let’s start with the significant one. The main reason for my visit was to witness the city’s transformation after nearly 30 years of bloody conflict. I wanted to see firsthand how Belfast had healed and evolved since the Troubles. Has peace truly taken root, and what does the city’s current reality look like?

The second reason is more whimsical. I have a peculiar fascination with cities that start with the letter B, especially those that have faced or are facing various challenges. It might sound odd, but cities like Beirut, Bagram, and Baghdad give me a unique thrill. So, you can probably guess which destinations are next on my list 😉

As we delve into the topic of this post, let’s begin with a brief historical introduction.

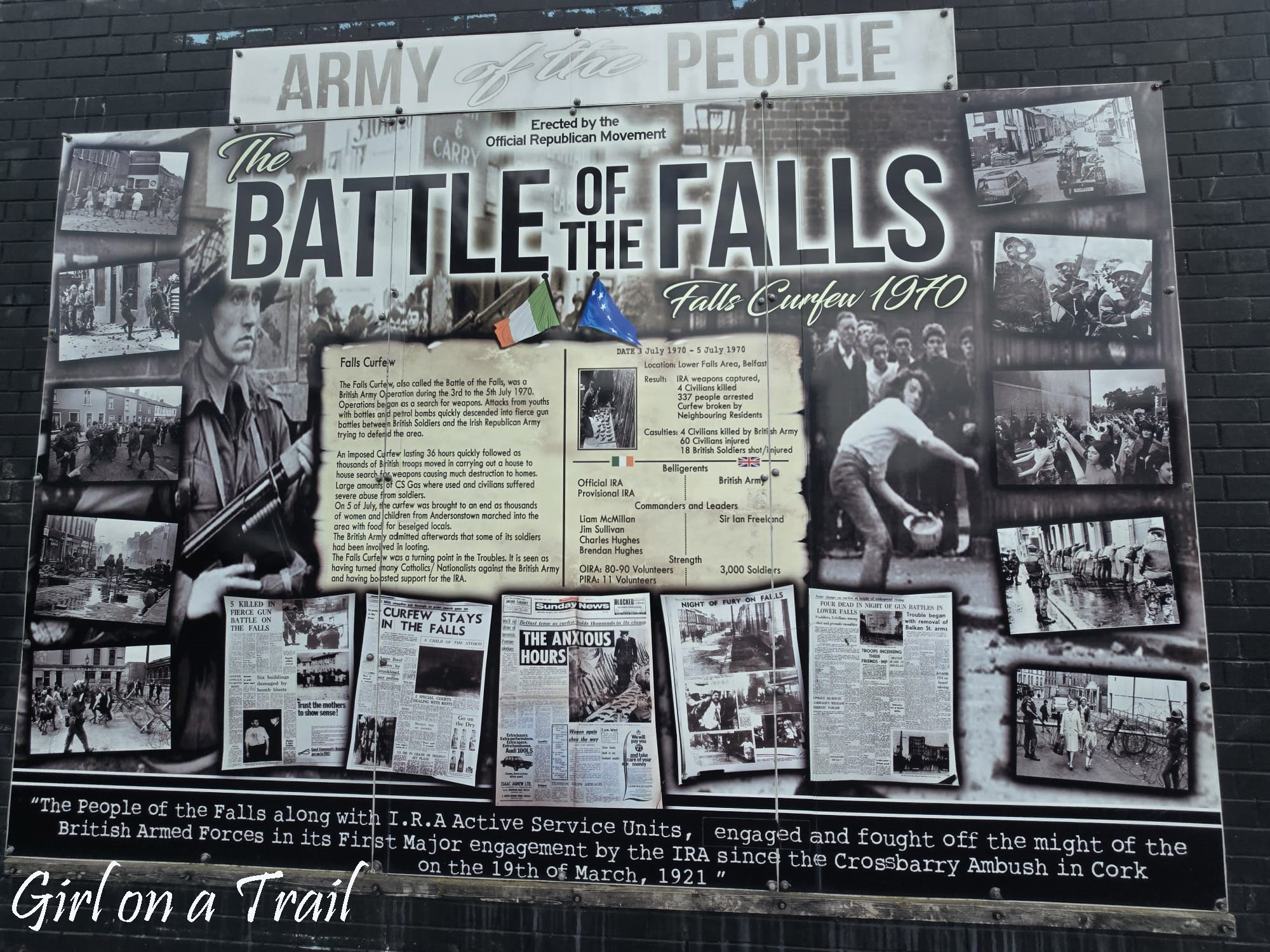

Conflicts in Ireland date back to the Middle Ages, beginning with the settlement of the island by the Kingdom of England. From the outset, Ireland strove for full independence, which it finally achieved in 1921. However, Northern Ireland remained within the United Kingdom. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) played an active role in the fight for freedom, and its subsequent goal became the liberation of Northern Ireland. The IRA was not solely a military organization; its political wing was Sinn Féin party.

The most tragic period in Northern Ireland’s history was between 1969 and 1998, known as the Troubles. The term “the Troubles” seems a rather inadequate description for three decades of conflict that claimed over 3,500 lives. This term was coined by the British, as the United Kingdom deliberately downplayed the internal issues to avoid showing weakness on the international stage. As with most global conflicts, religion was conveniently used to justify the Troubles. They were portrayed as a religious conflict between Catholics, also known as Republicans or Nationalists (the Irish), and Protestants, also known as Unionists or Loyalists (the British). However, the primary reasons for the bloody strife in Ireland were territorial and social issues.

However, to truly understand the reality of Belfast, it’s essential to know the history of its notable places. One such place is the Crown Liquor Saloon, the most famous pub in Belfast. As you enter, you’ll notice a distinctive mosaic on the floor depicting the British Crown.

Apparently, the bar was named according to the wishes of the owner’s wife, who was a unionist. Meanwhile, the owner himself—a republican—placed the crown on the floor as a form of protest, so that customers entering the bar would step on it.

Opposite the pub is the Europa Hotel, nicknamed the most bombed hotel in Europe. Since its opening in 1971, it has been bombed 36 times. The hotel appears in season three, episode 11 of the TV series “Sons of Anarchy.” Right next door is the Grand Opera House, which has been targeted by bomb attacks only twice.

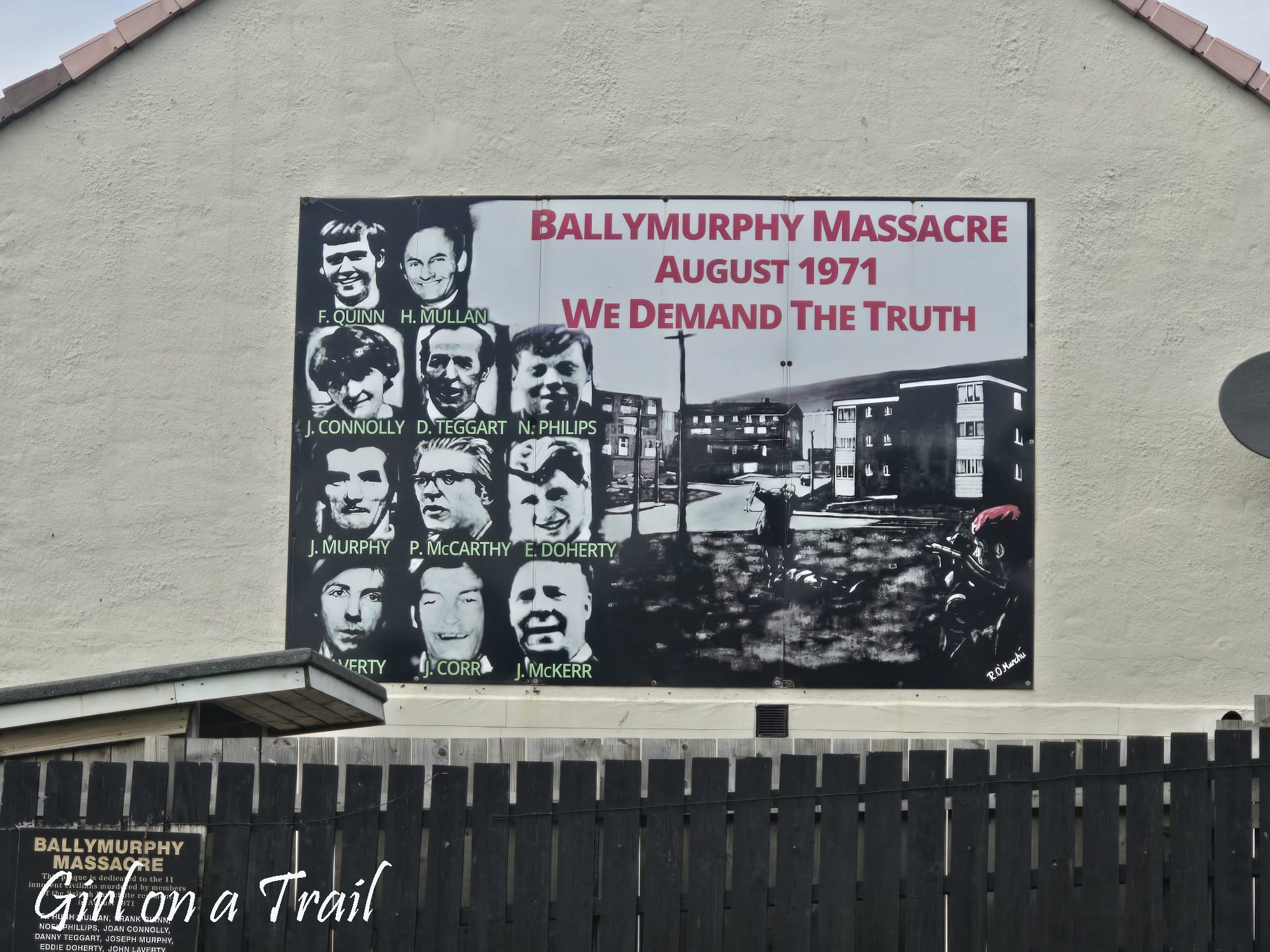

The next day, I continue my tour of Belfast, starting in the southern part near Whiterock Road. The walls are adorned with murals and posters that serve as a manifesto of the local community. Interestingly, not all of them appear old; some look as if they were created recently.

Many of the murals reference the general right of nations to self-determination and the respect for human and minority rights. It’s evident that republicans identify with other oppressed nations seeking justice.

Heading north along Falls Road, I reach the so-called Interface areas, the flashpoints where republicans and unionists live side by side. To prevent conflict escalation, “Peace Lines” have been established here. These walls, which can be made of brick or steel and are 6-7 meters high.

It’s impossible to cross directly to the area inhabited by unionists; I have to go back to find a way around the wall. However, I manage to “cheat the system” by finding an open gate.

The Peace Line walls can be seen in many places. During the day, they remain open, allowing the free movement of pedestrians and vehicles. However, in the most volatile areas, they are reportedly still closed at night.

Meanwhile, on the other side – the republican one, the murals appear to be much more radical. The most prominent ones can be found on Shankill Road. It was here, during the Troubles, that a gang of serial killers known as the “Shankill Butchers” operated, brutally murdering randomly chosen victims from the republican community.

Many murals glorify the activities of the UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force), a terrorist-paramilitary organization of Northern Irish unionists that still remains active. The UVF orchestrated terrorist attacks targeting republicans. Meanwhile, on the republican side, only a handful of murals mention IRA.

A place that particularly divides republicans and unionists is the city of two names: Londonderry and Derry, located right on the border with Ireland. Derry is the name used by republicans, while unionists prefer Londonderry. (London)Derry is one of the largest cities in Northern Ireland. Its main tourist attraction is the defensive walls built in the 17th century. Reportedly, these walls were never breached and remain one of the best-preserved fortifications of that kind in Europe. However, few tourists coming here have heard of this attraction. The city is mainly associated with an event known as Bloody Sunday.

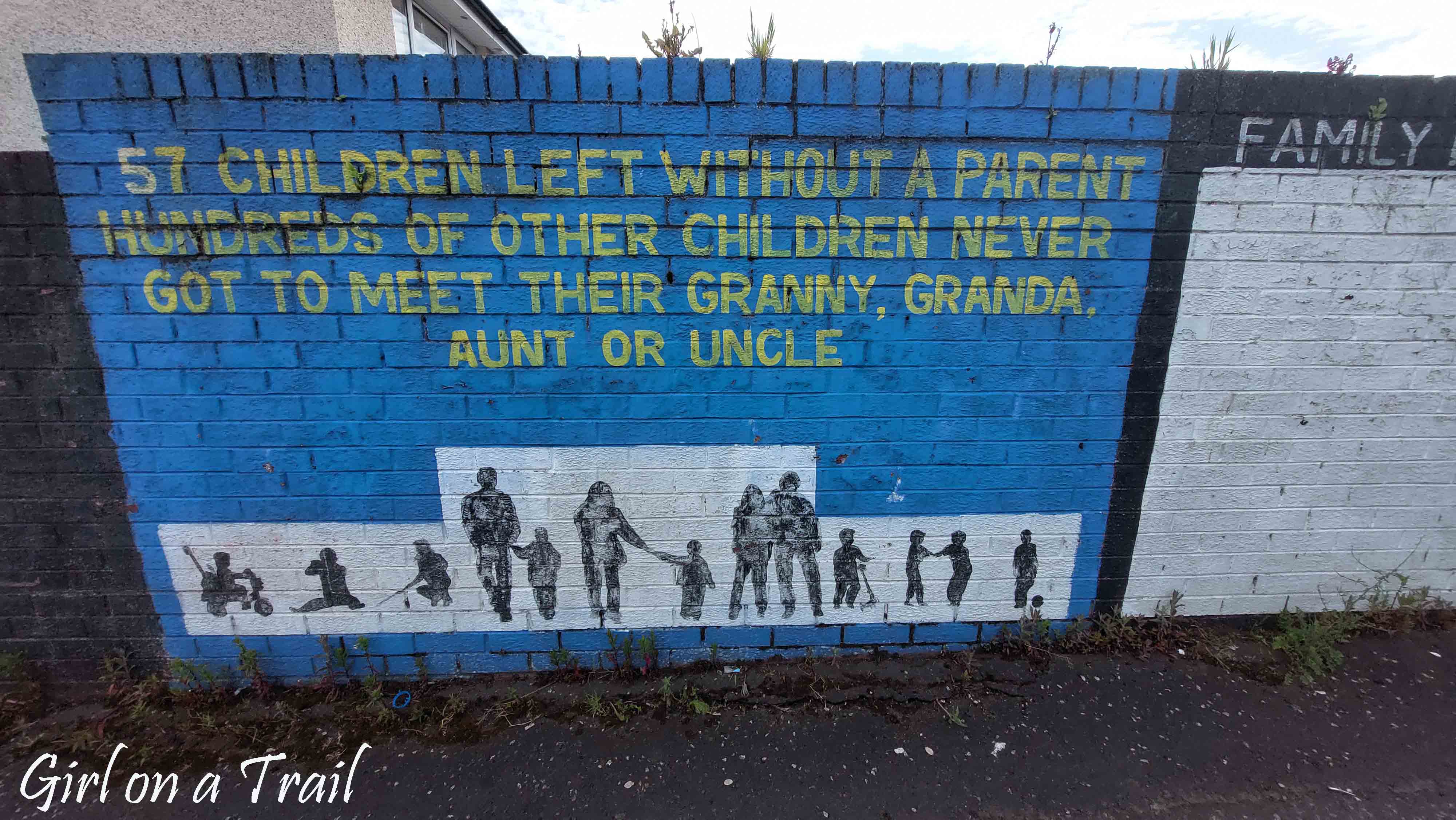

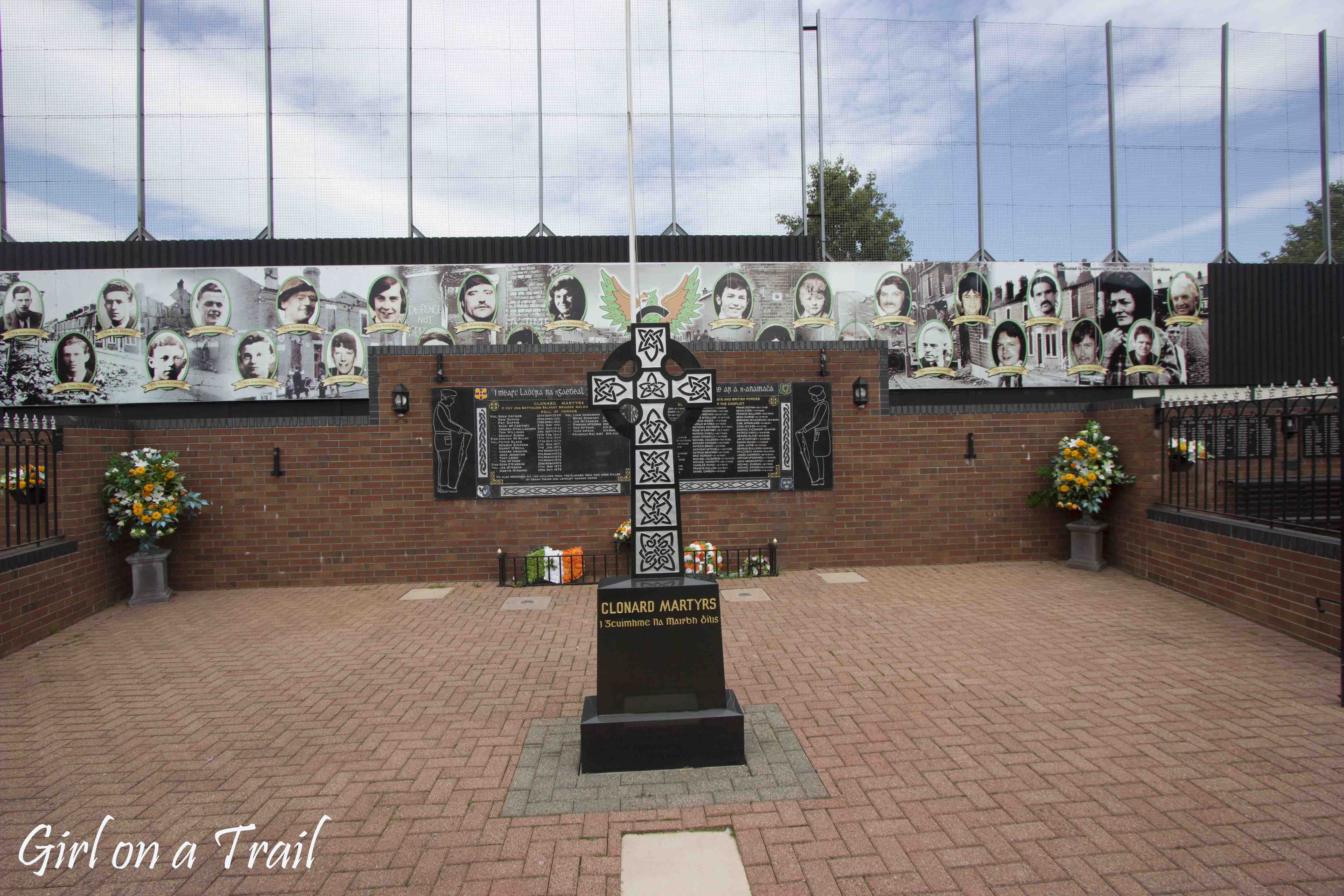

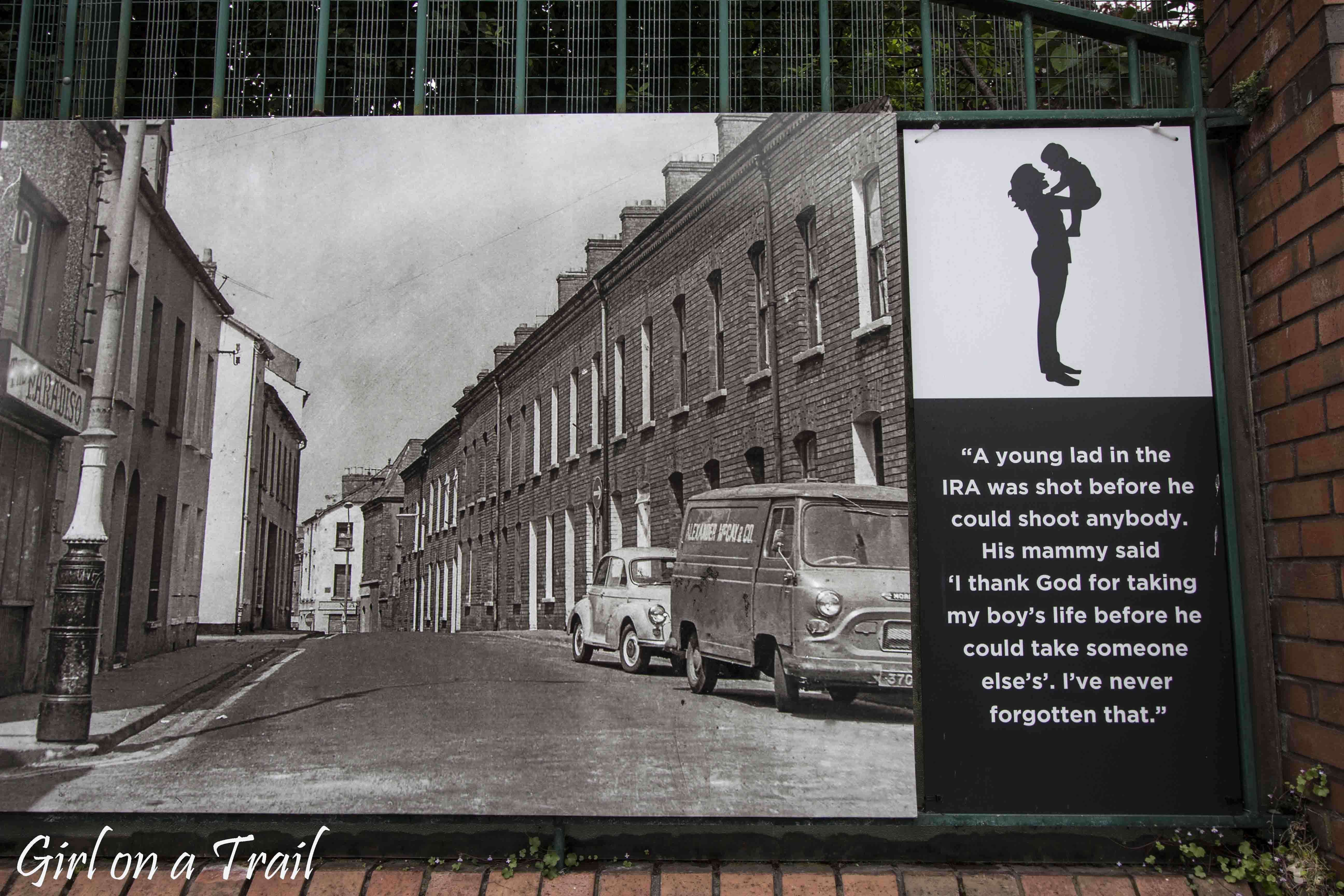

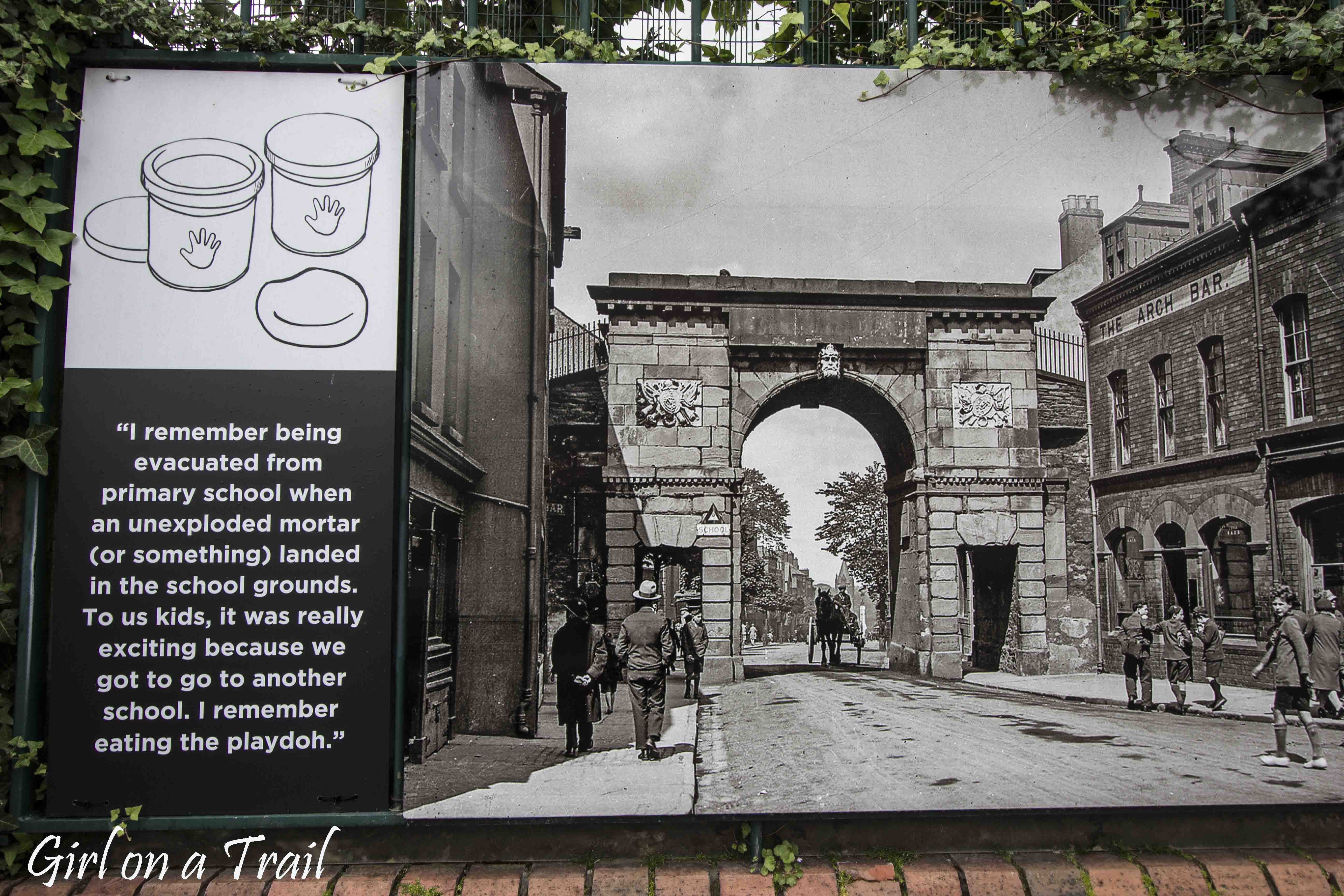

On January 30, 1972, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) organized a peaceful protest against a law allowing British authorities to intern people without trial. During the protest, riots escalated, leading the British Army to open fire on the crowd. As a result, 14 people were killed. Bloody Sunday heightened hostility towards unionists and intensified the actions of the Provisional IRA. The memory of this event remains vivid among residents. Black-and-white photographs with poignant descriptions can be seen on fences, serving as a reminder of the tragedy.

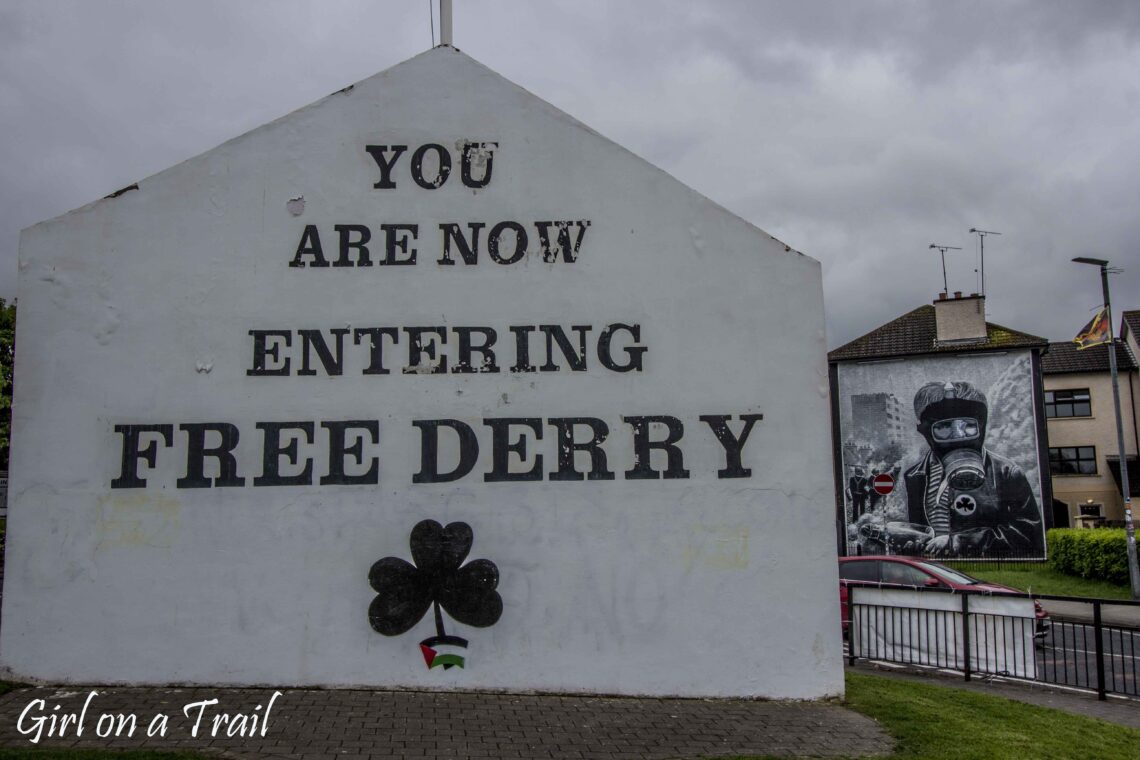

The history of Bloody Sunday can be explored at the Free Derry Museum, which opened relatively recently, on June 15, 2017.

Nearby the museum, numerous murals and posters serve as reminders of the dramatic history of (London)Derry. Of particular note is a mural depicting a young boy wearing a gas mask and holding a Molotov cocktail. It was painted in 1994, during the onset of peace talks.

However, what caught my attention the most were the posters scattered throughout the city. They indicate that the conflict has not ended and that the memory of the bloody events is still deeply rooted in the consciousness of the residents.

Similarly to Belfast, one can also observe that the republican community supports the independence movement of Palestine.

To sum up, despite many years passing since the end of the conflict in Northern Ireland, the memory of the Troubles seems to remain vivid among the residents. Both the center of Belfast and (London)Derry appear to be vibrant, welcoming cities. However, upon closer look, signs of social tensions that led to the Troubles can still be discerned. It appears that the Troubles still exist but are swept under the carpet.

Find out more about Northern Ireland here.